Why It Won't Stop

Out-of-state giving now dominates political fundraising

Summary

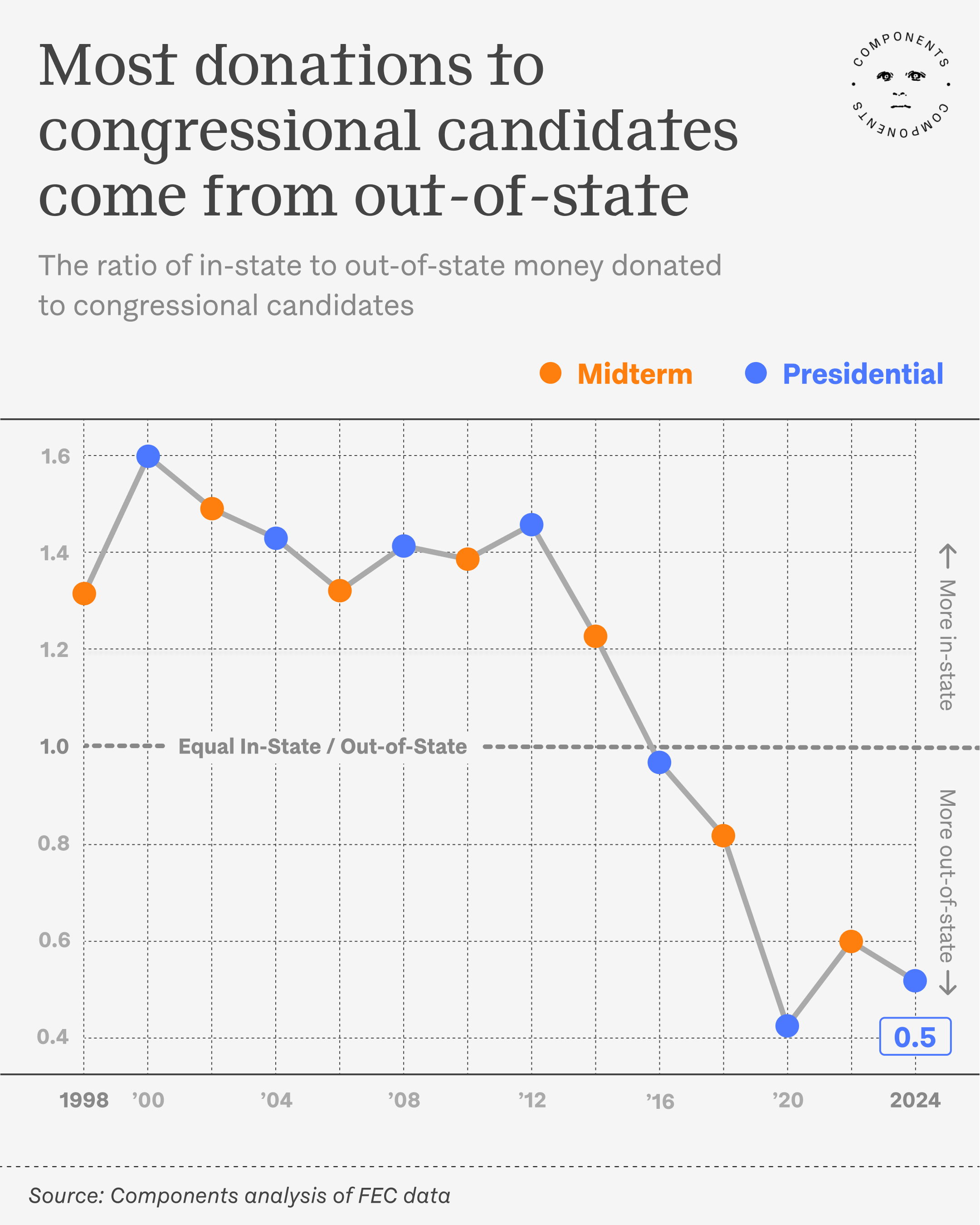

- Individual, non-PAC contributions to congressional candidates are now more likely to come from donors who live outside the candidate’s state than from in-state residents, at a roughly 2:1 ratio, a Components analysis finds.

- This balance was tipped in 2016 and the trend has accelerated since.

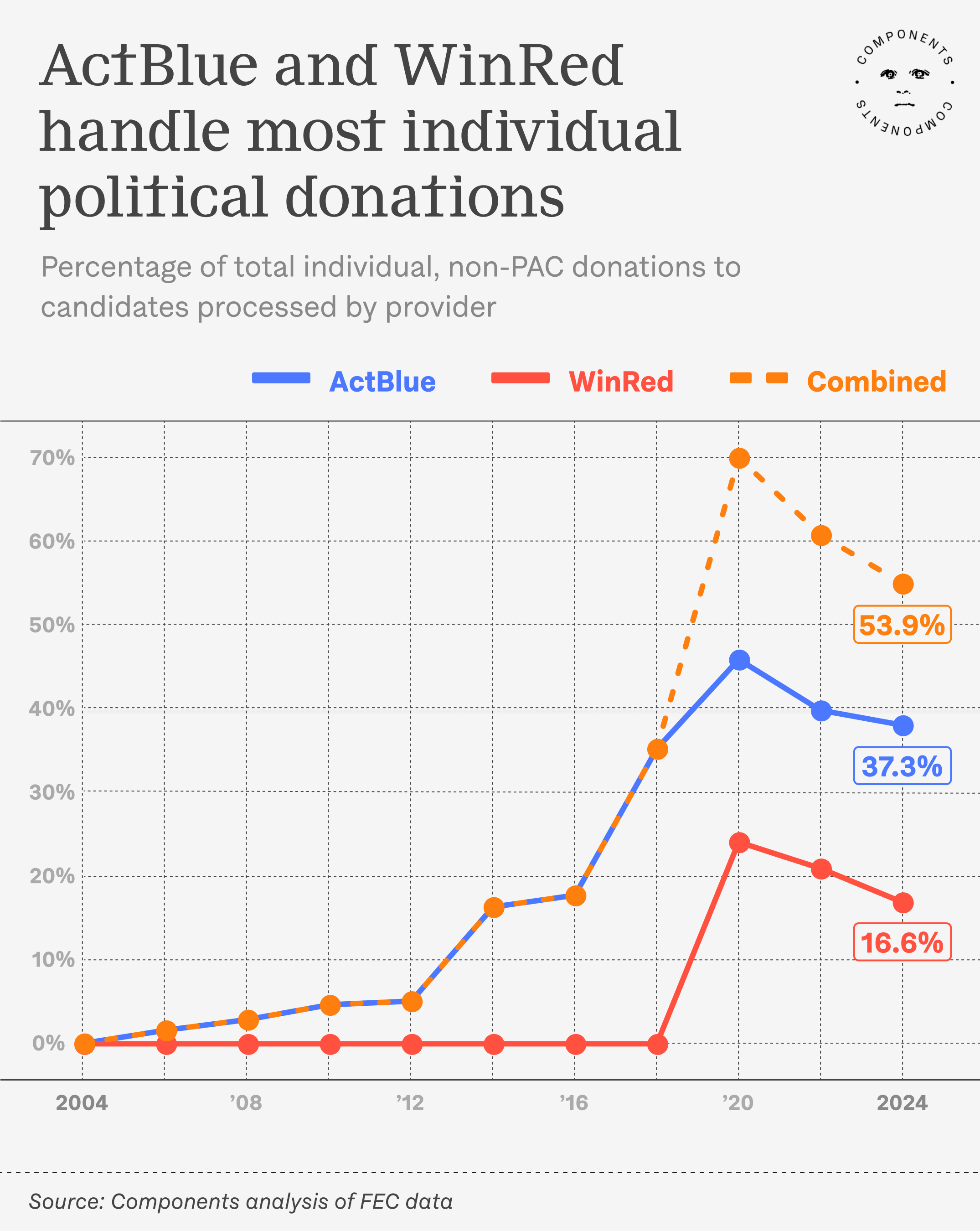

- The primacy of out-of-state gifts has been facilitated by the rise of ActBlue and WinRed, which in the 2024 election processed about 54% of all campaign contributions

During an election, you will receive dozens of text messages from political candidates soliciting a campaign contribution. In 2022 alone, 15 billion political text messages were sent — meaning the average phone received 50 of them. Your area code and actual place of residence has little bearing on which candidates will appeal for a contribution. Live in California with a New Mexico area code? Meet “Sarah Trone Garriott: a mom, minister, and Democratic State Senator running for Congress to fight for Iowa families and take on the broken politics in DC.”

These out-of-the-ActBlue solicitations are tailored to take advantage of the growing share of donations to congressional candidates that come from outside the state they’re actually running in. An early sign of the shift came in 2019, when the retired Marine colonel Amy McGrath released an ad online to announce her intention to seize one of Kentucky’s Senate seats from Mitch McConnell.

In the 24 hours after McGrath’s ad went online, her Senate campaign received $2.4 million in donations. Over the next year and a half, her campaign would raise almost $100 million dollars on the way to an absolute drubbing by McConnell, all that money helping her only outpace Joe Biden’s performance in the state by about 40,000 votes.

McGrath has hardly been the only longshot candidate to raise such an extraordinary sum of money. Two years later, Democrat Jamie Harrison raised $57 million in one quarter as he sought to unseat South Carolina Senator Lindsey Graham — a race that also ended in a predictable blowout loss. Candidates posting these eye-popping totals for congressional campaigns they have little hope of winning is indicative of the nationalization of the electorate, with partisans eager to throw money at anyone who promises to take down a partisan bogeymen — McConnell, Ted Cruz, or Lauren Boebert on one side, Nancy Pelosi, Alexandra Ocasio-Cortez, and Elizabeth Warren on the other. In the George W. Bush era, someone running for the House or Senate might expect to receive one dollar from an out-of-state donor for every three they raised in-state. Now, that ratio has inverted, with overall out-of-state contributions in 2022 nearly doubling what candidates could raise in-state.

In many ways, the nationalization of the electorate follows the same arc of placelessness as all other facets of 21st Century life. If the average American is now more familiar with Marjorie Taylor Greene or Ilhan Omar than they are the people running their city or county government, it’s for the same reason they’re not familiar with much of anything in actual proximity to them anymore. But regardless of how much weight one chooses to put on any particular we-live-in-a-society critique, the growing propensity of donors to support candidates who live in different states appears to be a lagging indicator of that shift. While the ratio of in-state to out-of-state spending was relatively stable from 1998 to 2012, it began changing as soon as the ActBlue payment processing platform was adopted by Democratic candidates all over the country. Along with its Republican counterpart WinRed, the two platforms accounted for 53.9% of all campaign contributions in the 2024 election.

ActBlue created a standardized way for liberal donors to support candidates, storing not only their payment information but the demographic disclosures required of any political donor. Once you had given to one Democratic candidate through the platform, it was a snap to give to another one, regardless of location. The extensive lists of individual donors generated by ActBlue have consequently become like collectibles to campaigns, with candidates purchasing lists of donors from each other until practically every campaign has practically every donor’s information. During the 2018 election cycle, a single donor named Sibyll Barlow made 4,877 gifts using the platform. While Barlow lived in Concord, a wealthy suburb of Boston, she told reporters from the Center on Public Integrity that practically all her donations had been directed out of state. Another ActBlue “super user” from California named William Nottingham said, “I can’t get in the car and drive to Kentucky and campaign for someone like Amy McGrath, but I can sure send her a couple of bucks now and then.”

Recognizing that ActBlue had created a massive grassroots fundraising gap between Democrats and Republicans, the GOP launched WinRed in 2019. Over the next year and a half, the platform processed $1.2 billion in donations to conservative candidates, a veritable West Texas gusher of political cash that the Republican rank-and-file had been eagerly waiting for an opportunity to spread around the country. Once fully operational for their respective political partisans, WinRed and ActBlue were able to process 60 percent of all gifts in the 2020 election cycle, setting a record for the election where the highest proportion of out-of-state money was raised.

In the years since, congressional candidates in hopeless races have become fond of touting their fundraising numbers, even as those windfalls represent little beyond rancor at their opponent. Democrat Adam Frish garnered national attention for his race against Lauren Boebert in 2023 when his campaign announced it had tripled her fundraising haul in one quarter; Republican Steve Garvey got a good news cycle out of his having outraised Adam Schiff by over a $1 million in their California Senate race.There’s some evidence that spending big on political advertising has more of an effect on determining the winner of down-ballot races than it does presidential elections. Still, the sheer quantity of money spent matters far less than the way that money is spent, and on whose behalf. While a new candidate for a local office can get a huge return on investment on their advertising if their main goal is simply introducing themselves to voters, it’s hard to imagine that was a major factor for a retired professional athlete like Garvey in his largely symbolic gubernatorial campaign. (Both lost). The same process is unfolding ahead of the 2026 midterms: this past summer, the retired Marine Corps sergeant challenging Marjorie Taylor Greene in Georgia proclaimed that his campaign had outraised the incumbent in the month of June.

Wishful thinking often motivates out-of-state giving, but it is also a useful barometer of grassroots enthusiasm. Take New York City’s mayoral race: more than half the $1 million Zohran Mamdani raised in a thirty day period came from outside the five boroughs, with most of that haul coming from small gifts — only one out of every eight donors actually lived in New York.

The ability of a leading candidate for a mayoral office (albeit one that governs a population larger than most states) to garner so much support from people who will never be his constituents is indicative of the desperate desire of so many Democrats to support a candidate — any candidate — who seems capable of pushing their party out of its stultifying routine. ActBlue and WinRed provide a tangible way for partisans across the country to converge on a single race and say, “More of this, please.”