There is inflation in the world but not in this room

The grim world outside has supposedly come for the club. The economics may speak otherwise.

Summary

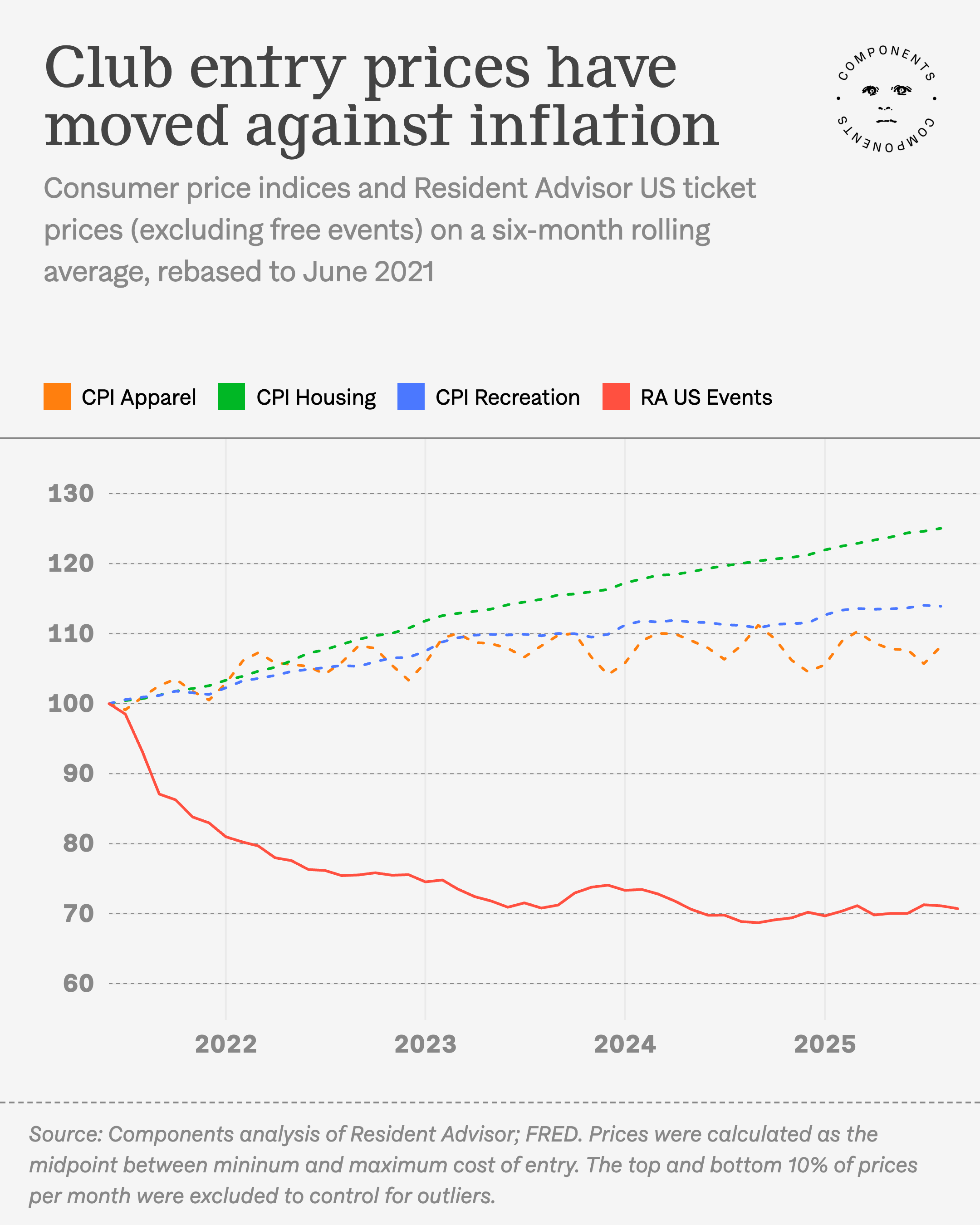

- The average ticket for a paid event on Resident Advisor fell about 30% from post-pandemic highs in opposition to broader inflationary trends, a Components analysis finds.

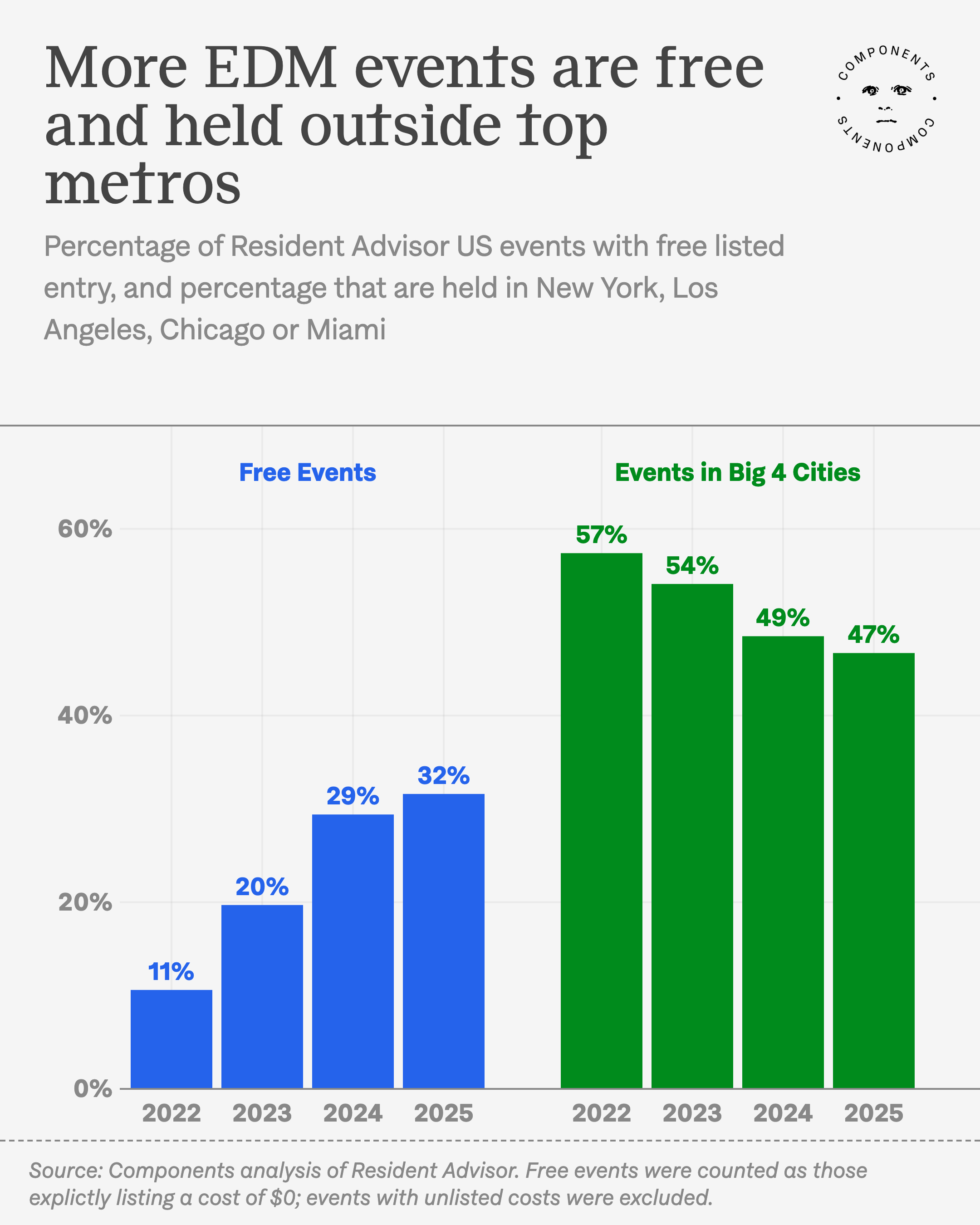

- Electronic music events on RA are increasingly likely to charge no cover, and to be held outside of NYC, LA, Chicago, or Miami.

- This all suggests that a recent renewal of interest in dance music has done more to inspire newcomers and DIY promoters than it has to encourage price hikes or corporate takeovers.

When dance music commentators are not writing about the music—and it seems they would take any excuse not to write about the music—they tend to be eulogizing it. Either 1) no one is dancing because everyone is on their phones, 2) no one is dancing because everyone is a DJ, or 3) no one is dancing because they're too busy theorizing about dancing. But if there is one unifying fear, it is that capital has turned nightlife into yet another asset under management.

Such concerns are nothing new,Between alcopop guerilla marketing and PlayStation chillout rooms, corporate sponsorship was a hallmark of the UK's turn-of-the-millenium boom years. The Guardian could declare that clubbing had "become the realm of huge multinational corporations and sponsorship deals" back in 2004. By the 2010s, EDC and EDM had hit their stride stateside… and on and on. but private equity firm KKR's incursion into clubland has brought institutional capital back to the forefront of dance music discourse. Op-eds and IG reels alike now cast dance music as the casualty of a historical progression that began with revolutionary acts in the Rust Belt and ended with slackjawed matcha raves in Hudson Yards. Allbirds stamping on a human face, forever.

It’s easy to buy into this resignation. Even the editor of Resident Advisor recently argued (convincingly!) that mainstream nightlife is in a retrograde cultural tailspin. But if total corporate capture were a given, it would presumably play out the same way it does everywhere else: with a hike in prices. Instead, the average cost of U.S. paid tickets on Resident Advisor has trended downward over the last four years, falling about 30% from June 2021.

Cover charges are an incomplete measure for the cost of clubbing, as anyone with a vodka tonic in hand can tell you. Even so, getting past the average bouncer has gotten cheaper. This is both a relief, and a reminder that nightlife has yet to be defined by Blackstone-bankrolled mainstages and VIP pricing tiers.

A world where more people can party for less money does not sound like such a bad thing. That any experience of any kind has gotten less expensive—or even just not gotten more expensive—is exceptional at a time where the cost of nearly every conceivable good and service feels like it has gone vertical.

There are pessimistic interpretations one can bring to this: it could very well follow from downward pressure on venue owners doing anything they can to bring people in the door. (Venues traditionally have the opportunity to recoup their losses at the door over at the bar, but a series of club closures indicates that it's hard to balance the books—not least because if Paragon doubled their prices like Cal-Maine Foods, Mondelēz, or the median landlord, they'd be crucified for it.)

Still, something particular is happening at dance clubs. After all, cinemas face the same headwinds, and have responded by jacking up the price of admission at the same rates as the rest of the U.S. economy. In its simplest form, then, the difference is that your typical promoter has no investors to answer to, and motives beyond dynamic pricing or profit maximization—two things you can’t say about your local Regal Cinema.

If there’s anywhere a price hike would be expected, it should be New York, which conventional wisdom holds is ground zero not only for bottle service and business techno, but for corporate pop-ups and superclubs financed by private equity. Whatever the moral or cultural harm of a Smirnoff pop-up in the outer boroughs may be, its monetary impact on the average raver Much of the popular writing I’ve seen on nightlife focuses (sometimes in hazy terms) on gentrification inside clubs. A less expensive average ticket price complicates that story, but doesn't speak to how clubs can drive gentrification on the outside, or how real estate valuations figure into that picture; what's good for ravers may not be good for their neighbors. seems limited: event prices in NYC are lower than they were in 2021, and have held steady over the past three years.

Even if KKR is deadset on ROI, one is less likely to be flying out to Sónar or getting guestlisted for Boiler Room than to be attending a local event. And those have gradually grown more common: 2024 was the first year of the decade where there were more events outside of NYC, Chicago, Los Angeles, and Miami than in them. There are as many definitions of a healthy underground as there are DJs, and there are more DJs every day, but a world with psytrance in Pittsburgh and liquid drum n' bass in Albuquerque must count for something.

More striking still is that free RA events have tripled in frequency over the last four years.This is true both of events explicitly designated as "free" on RA (which still represent a relatively small share of listings) and those without price data (which outnumber both "paid" and "free" events). Some portion of this may be made up by dive bar vinyl nights and K-Pop Demon Hunters karaoke events, sure. But this also points to a long tail of ravers, casuals, and true believers who cannot (or will not) ask or pay $40 at the door, and who, accordingly, make poor targets for corporate takeovers.

The boycotts that were organized against KKR/Superstruct are one good reason not to catastrophize about the state of nightlife. That financial gatekeeping has not come to define the scene is another.

Cultural critics often can't help but proclaim doom from all angles. Sometimes things really are as bad as they say. As far as the music industry goes as a whole, it's certainly not all in their heads: Just about every other sector of it has been scrapped for parts, from catalogue purchases and sync deals all the way down to advertorials and sponcon.

But other times, it's simply because they can't help it, because doom is the genre, because a personal melancholy is projected out towards everything that exists. In 2011, Mark Fisher's name was synonymous with critical acumen. In 2025, it can evoke a subtle roll of the eyes, and maybe just did. For all his virtues, Fisher told us that the entirety of musical creativity died circa 1993 and that everything that has ever followed is a mere loop of nostalgic regurgitation. This claim inspired a good portion of a generation of critics to say the same thing despite it being so obviously, demonstrably wrong, and it's perhaps why he and the dialogue he inspired now seem so distant.

There's no reason to believe we won't look back on every death-of-rave commentator in the same way; like all apocalypse preachers, it's hard to keep listening when you wake up the next morning and realize Judgment Day never came. So long as Spotify and Live Nation exist, there will be myriad opportunities to pen missives about total corporate dominion over independent youth culture. But the dismal economics of streaming or mainstage dynamic pricing don't have to follow you to the dancefloor.