The Desire Distribution

Substack’s revenue curve, the end of the winner-take-all media markets, and the cleansing power of money.

Summary

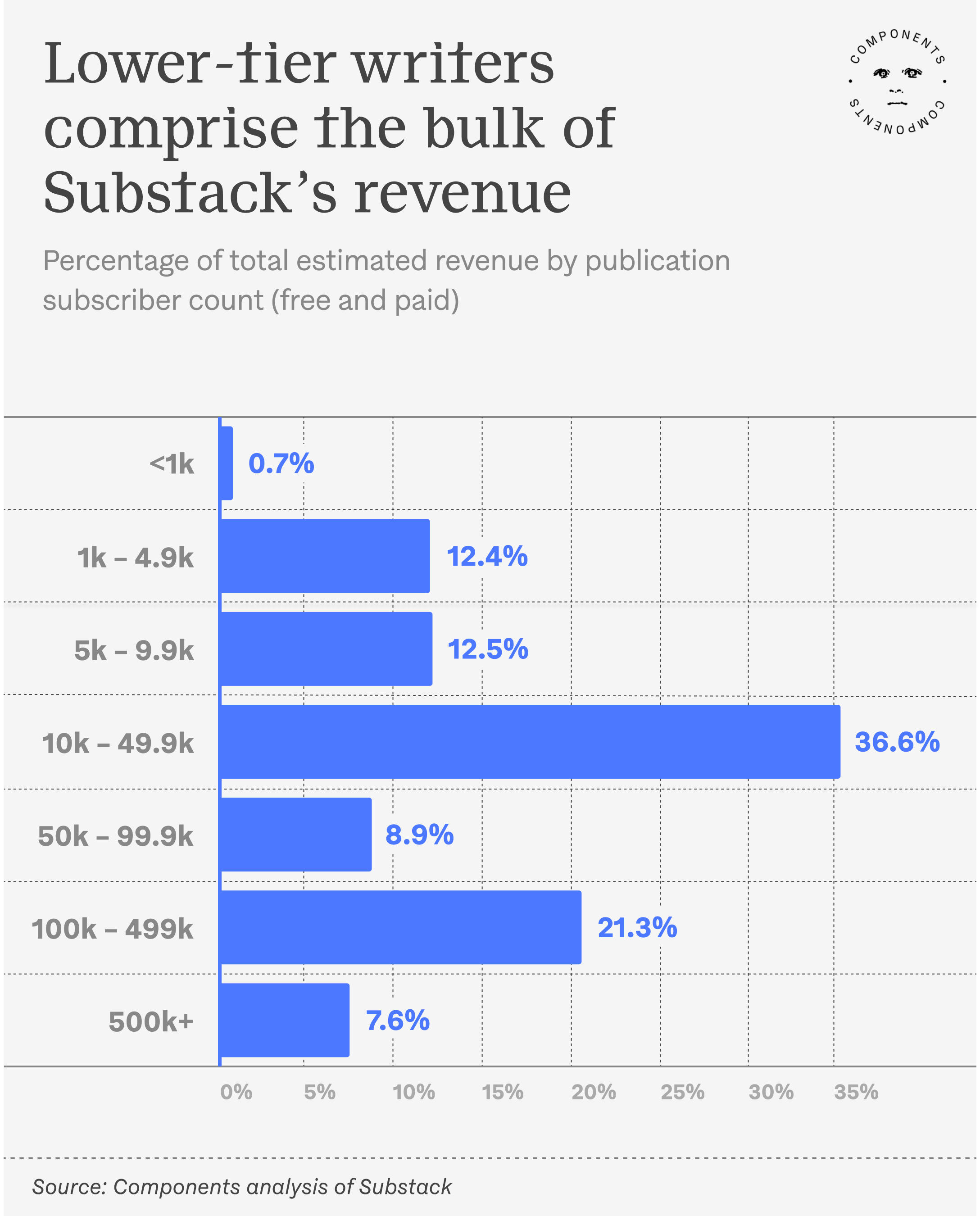

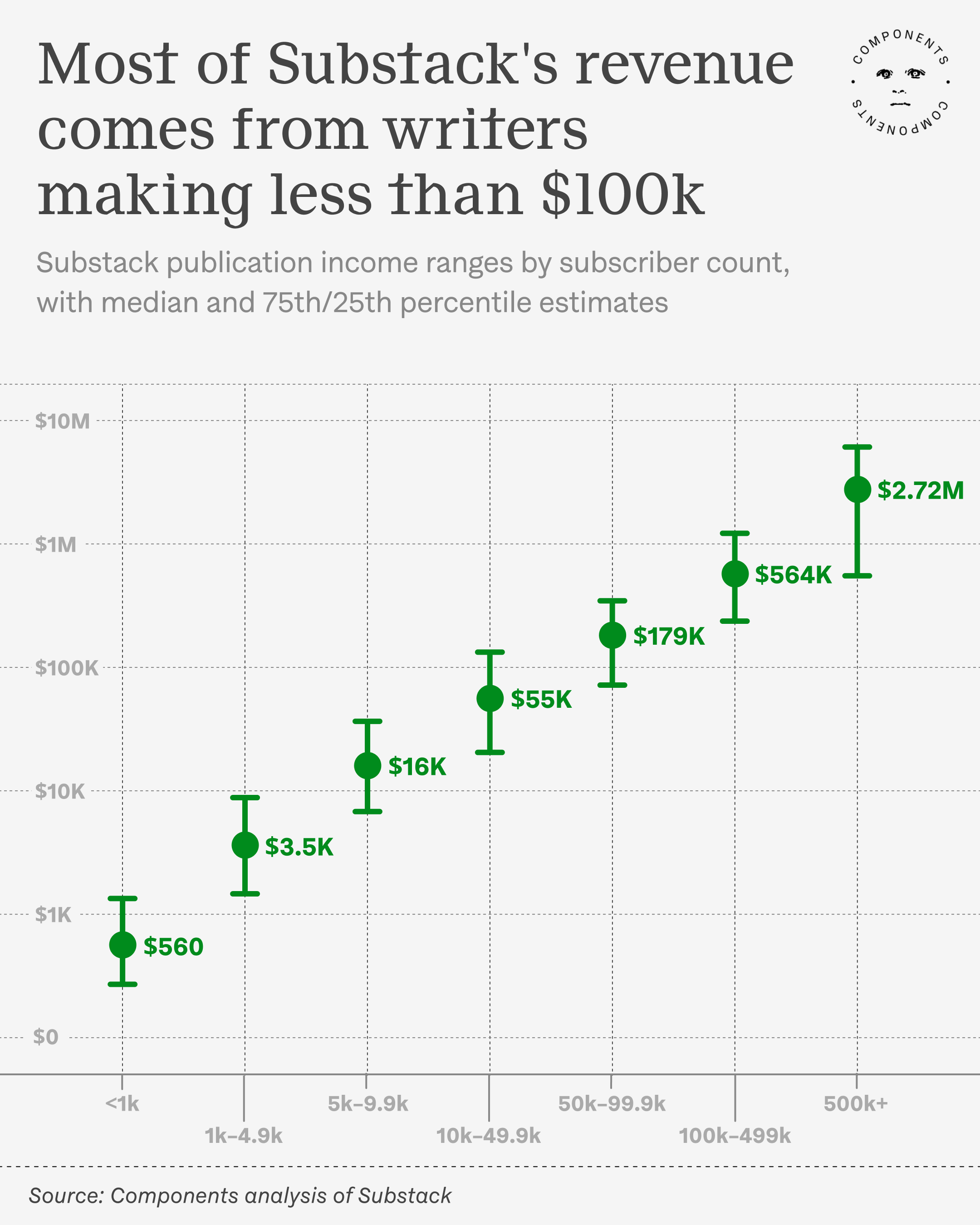

- A Components analysis estimates that about $600 million will be spent on Substack subscriptions this year.

- 71% of the money passing through Substack was spent on publications with fewer than 100,000 subscribers — a reversal of the fat-tail revenue distributions that have defined the platform age.

- This reversal stems from Substack’s reintroduction of money, rather than attention, as the basic unit of exchange, creating a market of need and desire particularized to groups rather than a broadly applicable media market appealing to biological reflexes.

Those who either lived through the 2000s or have graced a used bookstore will likely recall The Long Tail, published in 2006 by then-Wired editor Chris Anderson amid the opening shots of the platform age. Anderson prophesied an imminently sanguine future of cultural dynamism unleashed by new mass distribution channels that rendered physical constraints all but meaningless. Whereas Tower Records and Barnes & Noble had to contend with limited shelf space and find the lowest common denominators of their various markets, iTunes and Amazon were unbound by the same limitations. Without the contingencies of physical stores, they could sell everything, and Anderson predicted that’s just what they would do.

To the extent people reference The Long Tail anymore, it’s typically to make a point of how wrong it turned out to be. On Spotify, 90% of streams go to the top 1% of artists.

One analyst estimated that only 0.25% of YouTube creators actually earn any money. The platforms offer everything, but people consume very little of what’s actually there. “It never happened. More to the point, it was never going to happen because the story was a fairy tale,” the music writer Ted Gioia wrote in a retrospective of the book. Of course the future didn’t work out as a Wired editor planned. What has?

But Anderson’s thesis rested on a subtle detail whose disappearance was difficult to predict: it assumed money would actually change hands between buyer and seller, that cultural economics would follow the basic transactional nature it had since transactions began. What he didn’t forsee was the intricate latticework of licensing deals and platform economics that froze that exchange and enabled a form of infinite, virtually free, always-on consumption, as well as how that consumption would be led by the mutually denigrating factors of adtech and recommendation systems to generate 10 gigatons daily of the ur-slop AI is now trained to reproduce.

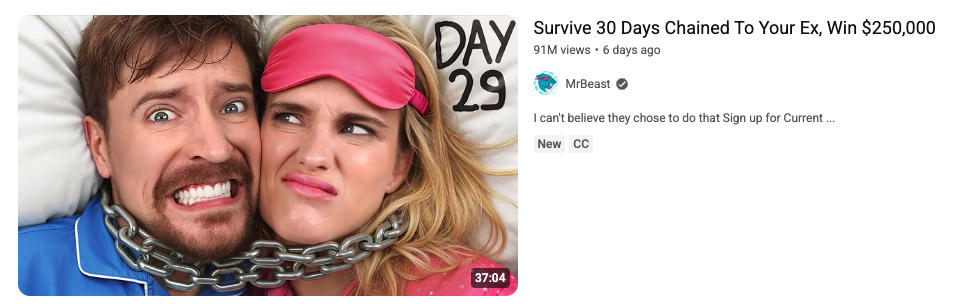

In other words, Anderson didn’t forsee the preconditions of the attention economy, whose existence has become such a basic fact of life that it has until recently become difficult to fathom the world without it.Easier to imagine the end of the world etc. In the attention economy, we pay little to no money, and instead engage in transactions of engagement, viewership, streams, and so on, with the the second-order effects of increasing ad revenue and/or continuing a habituation to a platform whose subscription fee is just small enough for us to not really notice. And as it turns out, what we pay attention to is fairly predictable. In the case of active attention, these are loud things, sexual things, shocking things, provocative things, annoying things, outrageous things. In the case of passive attention, these are things we can mostly ignore that hit some sweet spot of palatability. Think MrBeast and Jake Paul in the former and Drake post-More Life in the latter. In both cases, by removing a direct exchange of money from the transaction between buyer and seller, a product moves from needing to be good enough to actually be worth paying for to just being either good enough to spend a moment absorbing or not so bad that you turn it off.

At bottom, this is because the things that merely garner attention have to do little more than activate a set of biological reflexes that are mostly shared from person to person. And since what grabs attention is fairly uniform across a population, what works for one individual is more likely to work for another person at scale. For example, imagine that, while reading this, you hear a bomb go off. Does it get your attention? Does it get the attention of everyone else in the room? It’s worth considering why there's only one answer to this, and it’s because the things that garner attention are mostly impersonal — regardless of any imaginable detail that constitutes the individuals in the room, everyone will stop and pay attention to the sound of the bomb. If you have a migraine, it’s all you can pay attention to, and you don’t have much choice in the matter, regardless of who you are. The behavioral psychologists first hired by Facebook and then hired pretty much everywhere else to maximize engagement all operate from the same man-as-biological-machine premise, that what increases engagement — what heightens and sustains attention — is a set of biological and neurological properties that apply to one person as much as another. It’s why notification icons are red, why users are predictably fed certain irresistibly activating content, and why whatever app you’re using is designed precisely as it is. If all that matters is grabbing the user’s attention, however fleetingly, then the lowest-common-denominator approach will always prevail.

But would you pay for that bomb to go off? Or for a 30-second video of a street fight in Baltimore? Or for the individual track of whatever ignorable ambient music is playing in the background? Probably not, because what simply captures your attention is not sufficient to be the thing you actually want.

One might expect Substack to continue on the same trajectory as what has so far preceded it. On paper, it almost seems like it should. Its $190 million in funding, which puts the company at a $1.1 billion valuation, comes from some of the same VCs behind the biggest platforms of the attention economy. Its role in publishing is now so dominant that it has germinated its own ecosystem of startups, like The Ankler, which last raised $1.5 million at a $20 million valuation. The pending acquisition by Larry Ellison’s kid of its most inescapable success story, The Free Press, implies a revenue distribution whose money concentrates at the very tip.

But unlike most platforms, Substack has not ended up replicating the gross imbalances of revenue. It has reversed them.

Publications with at least 500,000 followersSubscriber numbers and revenue were calculated by sampling actual public subscriber info and a sample of a publication’s normal and founder-level subscriber rates and scaling that based on a publication’s size, not simply by applying blanket assumptions of how many people pay for Substacks overall. make up only 7.6% of the roughly $600 million we estimate was spent on the platform in July on an annualized basis. The bulk of that revenue comes from much smaller writers. More than 36% of the platform’s revenue comes from writers with 10,000 to 50,000 followers, who typically make anywhere from roughly $25,000 to $125,000. 71% of the platform’s revenue comes from publications with fewer than 100,000 followers.

Why would a platform built on users paying for products construct a negative image revenue curve relative to other platforms? Because unlike what merely commands our attention, what we purchase is on some level particular to the individual.Also I believe the philosopher John Dewey would see a distinction here between impulse and impulsion, with impulse/attention as mere reflex, and desire/need as a drive towards consummation. A purchase — for a barrel of petroleum, a shitcoin, a donation to a political candidate, a Labubu, or a copy of Madame Bovary — is a belief in that thing’s necessity, however small, either as a means to an end or as an end in and of itself. Sometimes that necessity is nefarious, sometimes it’s not, but it always begins with a desire that the purchase, directly or otherwise, seeks to fulfill.

These needs and desires follow the contours of groups and individuals and their own positions in the world in a way the universal dynamics of attention can’t. A private equity analyst needs information that a nurse doesn’t. A gamer wants to play Ghostwire: Tokyo, a quilter wants to make a quilt, a NASCAR driver cares about tires and stuff, and to you, your lover is the most beautiful person in the world. Attention has few optima, desire has many. A bomb going off means the same thing to me as my neighbor, but a screen of bond yields means essentially nothing to me and everything to a bond trader. All of them possess value from the point of the valuer, and contained in all things of value, one way or another, is the promise, immediate or downstream, of more richly being in the world. It’s why a well lit apartment costs more than a poorly lit one, why the promise of a life clad in Brunello Cucinelli in the Hamptons drives someone to go all in on a memestock, why at least many of us still spend money on the full experience of cinema instead of streaming on an iPad, and why we read things that, however slightly, transfigure the world into something meaningful from one’s particular vantage.

And so to buy anything,People of course pay for things like Spotify, but more as a low-cost utility than as some specific object of desire. including a Substack subscription, is to make an affirmative claim on a thing’s ability to somehow do that. Think of a Substack you subscribe to. Maybe you don’t subscribe to any. Okay, I’ll go: I subscribe to Spoils of War, a chronicle of the military-industrial complex by its sharpest observer, Harper’s Washington editor Andrew Cockburn. Cockburn’s newsletter is, for my money, the best documentation we have on how American tax dollars are recreationally lit on fire towards no betterment of national security. And when you finally grasp that the point of American war is not to win, but simply to keep fighting, as well as why forever war is the end goal to the point of compromising every other national interest, and when you understand the extent and mechanisms through which that happens, America makes much more sense. Everything in your environment — the destitute landscape of the country, the crumbling infrastructure, the pundits shrieking about Iran, the feast-or-famine social order — emanates significance that it would not have had otherwise. In other words, the environment becomes richer, deeper, more meaningful, more navigable.

The same basic value proposition is at play even in the most seemingly utilitarian cases. Substack has plenty of stock picking newsletters. I have no idea what their track records are, and even if they’re not good, the promise they hold is still basically the same as the promise of Cockburn’s newsletter: a way to make a landscape of objects intelligible that would otherwise be unintelligible, and therefore, a compass to navigate through them towards some end.

These needs are as diverse as the collective varieties of people and groups, and, as Components has argued about Bandcamp, Substack, whether cofounder Hamish McKenzie grasps this or not, is built on capturing the complexity of desires instead of the simplicity of attention, using relatively basic technology. That Substack is quickly vaulting towards a billion dollars passing through its platform in the next couple years while Vice navigates bankruptcy court, BuzzFeed sits inches away from becoming a penny stock, and every other media outlet that tried to chase traffic by following the rules set by the attention engineers of the platforms they circulated within, is, beneath the failures of the individual companies and the caprice of changes to Google’s algorithm,The perennial scapegoat of every media company’s problems. the endgame of a media economy where simple transactions in service of needs vanish.

So if Substack’s success is any indication, markets only work — and the long tail only finally appears — when money resumes its primacy and displaces second-order, intangible exchanges. “My experience is that money and transactions purify relations; ideas and abstract matters like ‘recognition’ and ‘credit’ warp them,Maybe the most striking about the article by the person who wanted to die because they didn’t write for BuzzFeed is how those participating in the attention economy internalize the need for that attention on a personal level. creating an atmosphere of perpetual rivalry,” Nassim Taleb writes in Antifragile. “Commerce, business, Levantine souks (though not large-scale markets and corporations) are activities and places that bring out the best in people, making most of them forgiving, honest, loving, trusting, and open-minded. As a member of the Christian minority in the Near East, I can vouch that commerce, particularly small commerce, is the door to tolerance—the only door, in my opinion, to any form of tolerance.”

Perhaps Taleb is slightly overstating things. But the basic assertion that money clarifies, that markets should serve the needs and desires of buyers and sellers, and that markets without money fail to do this, is difficult to refute after more than a decade of its absence. A dying media industry in New York is trying to refute it anyway, chasing algorithms and blaming them when things don’t work out. In an interview, McKenzie gave much of the industry five more years before it finally collapses. They should cherish every day they have left.