Put the Money in the Bag

Clothes listings struggle to sell on fashion resale platforms. Purses are another story.

Summary:

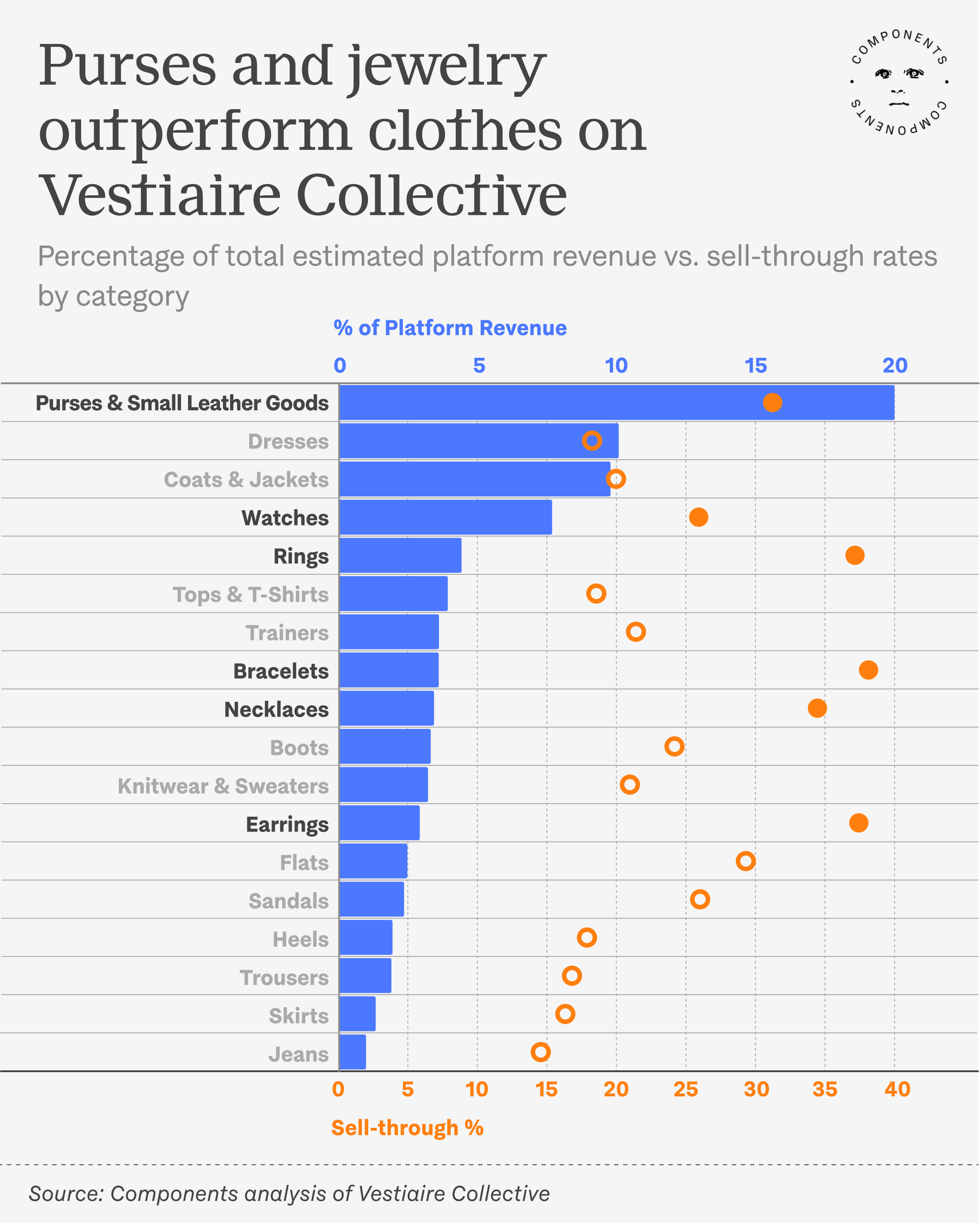

- Online resale startups created new markets for old clothes. But on Vestiaire Collective, purses, watches, and jewelry are most likely to sell.

- These categories represent about 16% of listings on the platform, but brought in 42% of revenue between March and September 2025, a Components analysis finds.

- That raises new questions about whether the broader sector can deliver on its environmentalist promises (or its valuations).

Online resale markets were built on the conviction that most things have value. They have yet to prove that most things are in demand. Consider clothing: Even at steep discounts or in “Like New” condition, the average Rag & Bone jacket or Naked & Famous jeans go unsold.

Purses are different. They’re the best-selling category on the luxury resale platform Vestiaire Collective, representing 11% of listings but a fifth of all revenue between March and September 2025—more than dresses, boots, sweaters, jeans and heels put together. Like other accessories, they’re not just more likely to sell than shirts or skirts, but to sell for a higher price, faster.

That is good news for anyone with a Longchamp to flip. For “recommerce” platforms, it’s a mixed bag.

Grailed, Thredup, Depop, The RealReal, Poshmark, Vinted, and Vestiaire Collective have spent the past decade making essentially identical pitches to investors (that they could capture a sliver of the billions that shoppers spend on clothing each year) and to sellers (that the neglected nylon button-up in their closet could net a few bucks).

But on Vestiaire, accessories sell best. Rings, bracelets, necklaces, and earrings each make up less than 1% of total listings, but combined, account for 15% of all revenue. These categories don't just command higher prices, but are more likely to sell at all, making them among the most profitable categories. If you couldn’t get mugged for it or use it to pay a bribe, it's less likely to find a home.

There is no shortage of explanations for shoppers’ skepticism toward secondhand shirts or jeans. What is harder to explain is what the future of clothing resale looks like if the sector’s best-performing categories succeed for all the reasons that they’re not really clothes at all.

The intuitive explanation is that rings, purses, and watches are less intimate. A handbag has many uses—you can festoon it with Labubus or carry a Pomeranian—but each takes place at arm’s length. Clothes, conversely, are broken in or worn out.

By the same token, accessories are one-size-fits-all. A secondhand Neverfull can be slung on any shoulder, a vintage Grand Seiko can be fastened on any wrist. Neither will shrink in the wash or stretch with wear—which is helpful if a shopper intends to “buy it for life,” but even more helpful if he has resale value in the back of his mind.

Vestiaire’s best-sellers have some overlap with duty-free kiosks and pawn shops, but the truest counterpart is Canal Street. Watches, purses, and rings sell well on both markets because they are standardized goods with high margins, recognized by buyers who are unwilling to pay retail prices. Importing a superfake may be more work than dropping off a bag at UPS, but for counterfeiters and resellers, the category merits the effort.

High margins are one reason that fashion houses produce purses in the first place. It is also the underlying principle that led the resale platforms (for all their FernGullyish language) to converge on being luxury markets rather than clothing markets. From processing fees to finders’ fees, a “designer” price point means that there's simply more cash to peel off each transaction. Most of these platforms (Vestiaire included) have banned fast fashion brands from their platform in order to maintain that standard.

However intently one holds The RealReal or Vinted to their “circular economy” promises, no one could fault them for taking steps to exclude threadbare sweaters or craquelured Gildan graphic tees from sale. No one wants to pay shipping & handling for chintzy shit. What is surprising, rather, is that even these painstaking efforts to maintain a curated selection at a luxury price point mostly can‘t keep shoppers from perceiving clothing as perishable.

Purses make this clear: While watches, rings, and bracelets are among Vestiaire’s most expensive categories per unit, the median purse is just $34 more expensive than the median dress (at a modest $173), and yet twice as likely to sell.

So no matter how much Vogue enjoys advising readers that Savette's $1900 Tondo hobo bag and Bottega Veneta's $5,500 Andiamo are the purses with “the highest resale value,” handbags outperform clothing not because they are ultraluxury "investment pieces" stitched by hand and built to last, but because shoppers perceive them as a different type of good at every price point. A higher price floor may keep fast fashion from gumming up the works, but is unlikely to close the gap between how we view clothes and how we view accessories.

This is, again, a mixed bag. Online shoppers’ enthusiasm towards secondhand purses and watches suggests they are convinced by Vestiaire’s authentication measures (no mean feat). Vestiaire’s decision to not warehouse its stock also means it will at least avoid being saddled with metric tons of unsold sneakers and sundresses.

But in the long run, shoppers’ reluctance to spend on secondhand clothes will remain a challenge for these platforms, whether or not the markets for luxury goods and startup funding continue to cool. The sector's struggles aren't new: Poshmark went public and was yanked back to private ownership within two years, The RealReal's stock price has only recently rebounded from a years-long slide, and four years on from its series F round, Vestiaire is still on its winding path towards a never-quite-there IPO. Last year, the platform took to the unusual move of crowdfunding from users, and just two weeks ago, founder and CEO Maximilian Bittner was ousted in a C-suite reshuffling.

The potential of clothing resale is clear in an era of extravagant waste and exorbitant pricing. But some skepticism is warranted about whether these startups will succeed in turning a profit—let alone “democratizing fashion” or eliminating those Salvation Army donation-box bleachfields—so long as the qualities that make its bestsellers perfect for resale are the same qualities that make them least representative of their broader inventory mix.

Of course, purses carry their own histories, no matter how well they sell secondhand. Any given handbag is a register of receipts and lipstick and loose metrocards, enough DNA and detritus from which to reconstruct a life from. Many a style reporter has tried, as in a noted 2006 profile of Mary-Kate Olsen in W Magazine, which pries into her Le City bag, finding it “dingy, covered with stains, pen marks, and even a chewed-up piece of gum,” and codifying a sort of louche glamour that has become de rigeur.

But two decades on, we’re still more willing to put up with the paraphernalia of a stranger's life than walk a mile in their shoes.