At any cost

New York is the one American city that only gets more expensive. In culture of predictability, why the demand for a place so unpredictable?

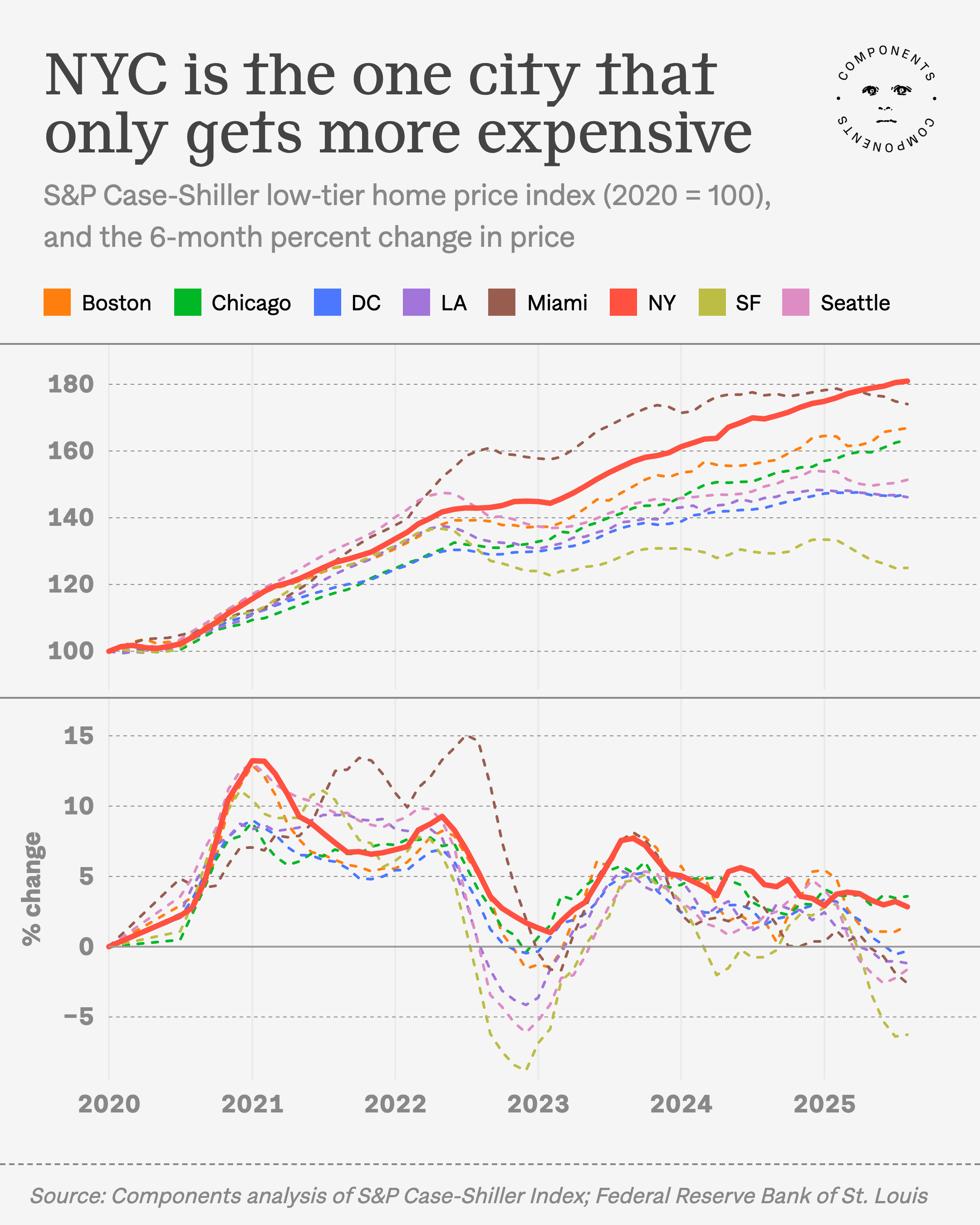

- New York City is the only major city in the U.S. that hasn't seen a decrease in low-tier housing costs since 2020, according to a Components analysis of the S&P Case-Shiller Index.

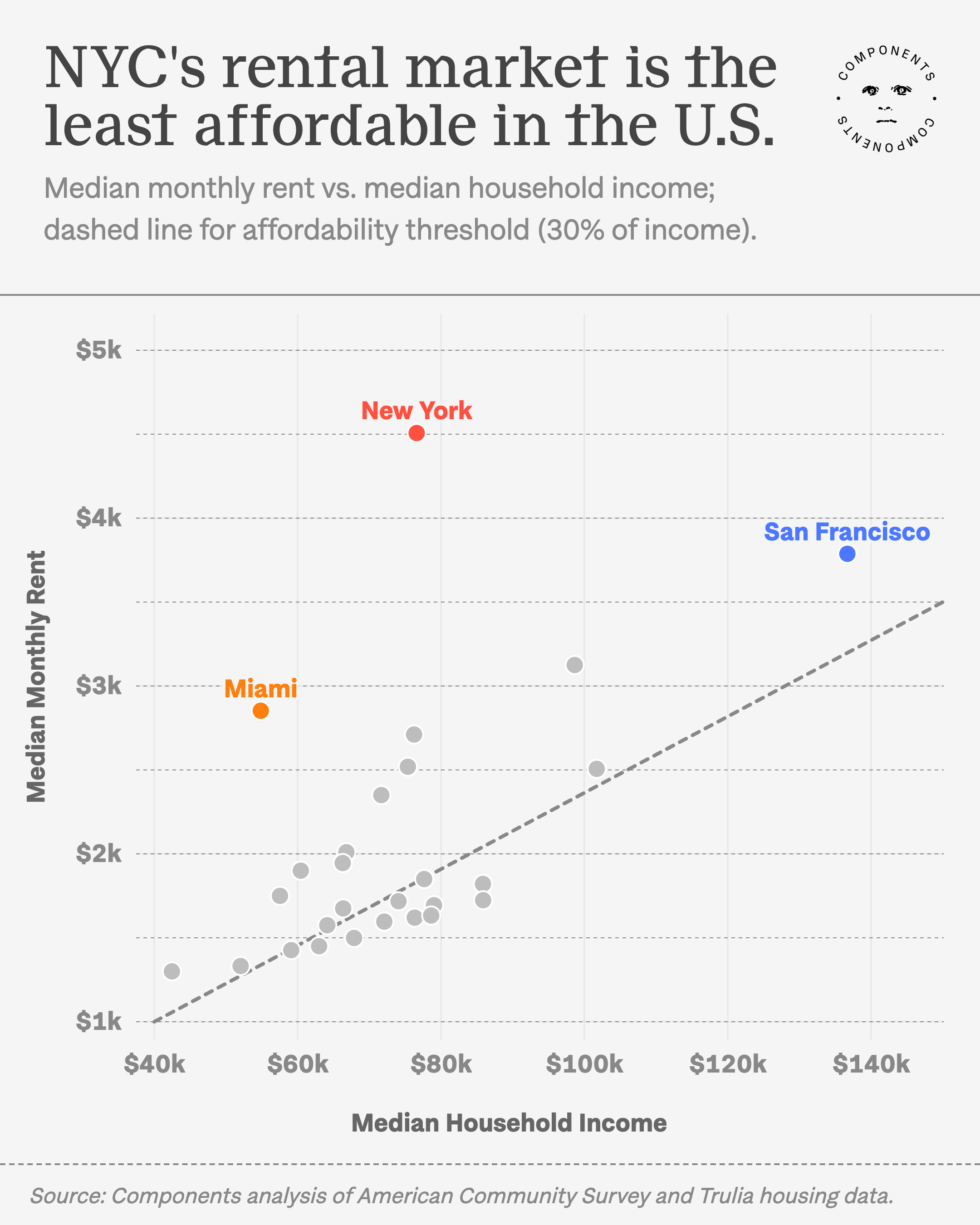

- It's also the nation's most unaffordable market for renters, as a Components analysis of the American Community Survey and Trulia housing data finds.

- NYC isn't the only city with supply constraints, but it is uniquely desirable, leading to the consideration that housing solutions may be better addressed from the demand side.

The “New York or Nowhere” tote seems to have reached peak popularity at a time when fewer people than ever can answer with “New York.” The basics of the city’s housing economics are now so familiar even to non-residents that they hardly bear repeating. Let’s do it anyway: In 2023, the city's vacancy rate hit 1.4%, the lowest level since the metric began being tracked in 1965. The vacancy rate for apartments listed for under $1,100 now sits at 0.39%. Its Gini coefficient continues to creep toward a perfect 1. As a result, Zohran Mamdani is now mayor.

While few markets have actually corrected from the post-pandemic inflation that has come to define American economic life, they have at least plateaued in just about every major city: Miami’s growth peaked in mid-2022 and has slowly stabilized. Remote work and new condos briefly cooled San Francisco's low-end housing market in 2021. Prices fell in Boston in 2022. Los Angeles and Seattle roughly followed the national average.

The exception is the place whose only alternative is nowhere. The lowest third of New York City home prices have climbed in every six-month period since 2020, according to the Case-Shiller Index. The sharpest growth is concentrated in this end of the market, which represents the only conceivable on-ramp to property ownership in the five boroughs, and where prices haven't actually declined since the 2010s.Prices in New York's low-tier housing market fell by 0.02% during the six-month period ending in January 2016, but for a sustained downturn, you have to look back to the Great Financial Crisis; the lowest third of home prices fell without interuption between 2008 and 2012.

The regulatory sclerosis, NIMBY obstructionism, and gentrification that breeds unaffordability is not unique to New York, nor is losing population: it’s estimated that 300,000 fewer people live in the city today than in 2020. Yet unlike San Francisco and Los Angeles, which each lost tens of thousands of residents during the pandemic, the price of homes in New York's housing market apparently only goes up, even with the addition of more than 100,000 new units.

In other words, New York’s housing shortage is considerably less mysterious and less singular than the fact that it is the subject of irrepressible demand. This leads (with gritted teeth) to the conclusion that New York is, indeed, special.That might seem pat were it not for a 2000s-era urbanist discourse that elided New York’s distinctiveness by folding it into a broader cohort of “superstar cities,” places defined by some combination of persistent economic growth and global cultural caché. It turns out places aren’t as interchangeable as per-capita gross metropolitan products would suggest.

What's so special anyway? If we take people at their word, it's singular and simple: It's the city where "anything can happen," which, again, would be mind numbingly banal to point out, except that conventional wisdom insists that "anything happening" is the absolute last thing people want. As this wisdom goes, what people want is predictability and certainty, experiences according to pre-selected settings, for the same thing to happen again and again like a child demanding you read the Berenstain Bears for the 25th time. This assumption — that people's true desires are to only meet a date they've screened ahead of time, to hear the exact sounds on wireless earbuds they've chosen in the rare event they leave the house, and to immediately hear the closest thing to Song A after Song A finishes — underlies almost the entirety of our cultural economy and its main tech stack.

This economy of certainty has customers because people do want this. Specifically, they want what we might call “uncertainty but not too much.” “Anything” can actually happen in an urban space if all your senses are actually open to it. You can find a quarter on the ground, see a dog in a terrific outfit, get robbed, miss an obvious opening with a beautiful woman that haunts you for the rest of your life. On Instagram Reels, two things can happen: You can see a video you like or not. On Hinge, you can match or not match. Maybe it’s theoretical overextension to say this is the same binary of the transistor within the tech stack itself creeping into culture, and we could spin around endlessly discussing why people have gravitated towards predictability. What matters is the paradox that the same people who every day choose certainty also choose to live in the most volatile city in the Western Hemisphere, no matter the financial and psychological cost, more than anywhere else in America.

If you live there, you see this paradox play out every day in a city that has essentially become a special economic zone of short-form video creators and indentured gig workers delivering burritos to people who never want to step outside navigate the canals between flagship stores and LLC-owned pied-à-terres. We are not the first to wonder why one would complete the Battle Royale necessary to move to New York for the privilege of ordering DoorDash at home and watching TikTok while walking down the sidewalk when, in all likelihood, your job offers you the opportunity to work from home, which you can do from anywhere and most likely do in your city apartment.

Here’s one uncynical hypothesis: People choose certainty on a quotidian basis, but on a larger scale they don’t really want it. People constantly choose things they don’t actually want on smaller units of time, and the things they actually want on larger units of time. Think of things done “in the moment”: using meth, committing murder, saying something cruel. No one spends two months planning to use meth or slight their lover, and if they spend months planning murder, that’s a specific mens rea with its own sentencing guidelines. So on a larger scale of value assessment, people are actually choosing the diametric opposite of our dominant cultural norm. While San Francisco has tech, Miami has tech and thongs, and Seattle has tech and redwoods, however much Jared Kushner and Bluetooth headphones have conspired to corrode it, New York still has more gestalt than pretty much anywhere else, or at least a lingering mythos of it. If it must be a company town, it is at least a company town for every company. And on that foundation, unexpected stuff — professional, romantic, experiential, and so on — happens.

That unexpected stuff may happen way less than it used to, but still happens more frequently than in any other city we’ve got in the country. And in this way, New York does (or did) what all generalist systems do — it puts everything in proximity to everything else, thereby producing a unitary whole that works better than any of those things in isolation. We could go on about how this defines all the best and/or most functional systems compared to their alternatives, from networks to contemporary AI models to human development itself. For now we won’t. The point is that when presented with a system of everything everywhere all at once, people choose it, and in choosing it, assign value to it. And the value people have assigned to the uncertainty and generalism either presently or imaginatively manifest in New York has proven to be inflexible in ways that demand for a conventional "superstar" metro area has not.

Whether all this is still extant in a city wreaked by a previously unimaginable asociality doesn’t really matter; the belief that it is a city of gestalt is the city’s value. The supply-side explanations for the city’s housing crisis are in every city in the country; the demand-side explanation is not. One can’t fully make sense of the city's only-goes-up housing market, and the emotional/psychological trials its residents withstand to endure it, without pricing this in.

At least on paper, Mamdani is committed to the former, promising to construct affordable housing and expand rent protections. These measures may or may not depress home prices, given that New York's market has proven immune to the factors that cooled growth elsewhere, but should at least provide some relief to the third of low-income New Yorkers putting more than half of their paychecks towards rent. In effect, though, he may inadvertently prevail more with demand-side solutions.

Or maybe Mamdani’s greatest achievement in turning the tide on the city’s housing crisis will turn out to be the simple act of being himself: a Muslim Democratic Socialist stoking the full spectrum of socioeconomic fears harbored by the city’s most moneyed and most detached class. Already, X is alight with the goodbye-to-all-that posts from people skipping town in order to avoid a 2% marginal tax increase. We first glimpsed this possibility in August, when a serial founder-turned-investor told one of us, “Mamdani scares the shit out of me.” It’s worth pointing out that this person did not live in New York.

It’s certainly possible Mamdani turns out to be a terrible mayor, as mayors almost always are. But he has already accomplished the once impossible demand-side housing challenge: for a certain type of pseudoresident, he has turned “New York or Nowhere” into “Anywhere but New York.”